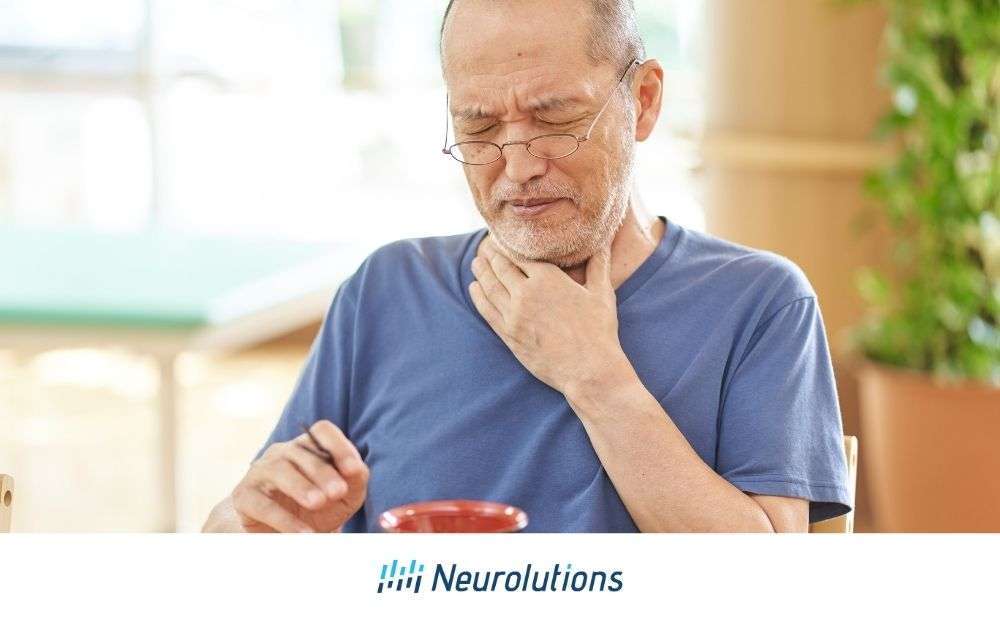

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a very common and often serious complication that can occur after a stroke. It happens when the muscles involved in the swallowing process are weakened or paralyzed due to damage in the area of the brain that is responsible for swallowing.

Because other effects of a stroke are more apparent–such as limb paralysis or weakness–dysphagia may go under-diagnosed. While it often disappears within two weeks in up to 40% of stroke survivors, dysphagia may persist for a lengthy time period or never resolve (1). In addition, the risk of pneumonia is highly increased in stroke survivors with dysphagia. Thus it is very important that stroke survivors and their caregivers know and understand the signs of dysphagia.

Stroke-Related Dysphagia: Recovery and Life Impact

Depending on the severity and location of a stroke, a stroke survivor may experience dysphagia. The areas of the brain responsible for coordinating swallowing are often vulnerable to damage during an ischemic stroke- especially in regions such as the brainstem or cerebral cortex (2). Because of this, those that have ischemic stroke (i.e. a blockage or clot that interrupts blood flow to the brain) are at the highest risk for dysphagia. The result can be a decreased ability to eat and drink normally, and/or severe pneumonia due to aspiration.

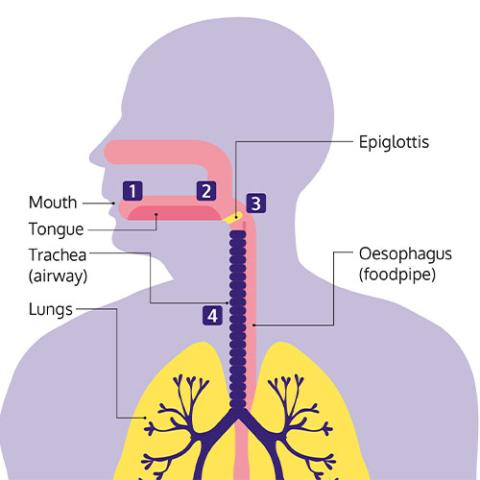

Aspiration pneumonia occurs when food or fluids go into the windpipe (trachea) rather than swallowed towards the digestive tract via the esophagus (3). When food enters the windpipe, this allows the bacteria naturally existing in our mouths to travel toward the lungs. Stroke survivors with dysphagia also may experience drooling, difficulty pronouncing words, and difficulty speaking in a loud enough voice to communicate clearly.

While only 13% of stroke survivors still have dysphagia six months post-stroke, long-term dysphagia is often linked to a need for solely liquid meals or a feeding tube to prevent malnutrition (4). Dysphagia is serious, and management requires a comprehensive approach. This article seeks to help stroke survivors experiencing dysphagia and their loved ones better understand how to attain a better quality of life using a prescribed dysphagia management program. Please note that your individual program will need to be tailored to your unique needs, and this guide provides a general overview of dysphagia management options.

Understanding the Connection: Stroke and the Complex Process of Swallowing

After a stroke, one of the two sides of the brain, or cerebral hemispheres, typically sustains the brain injury. However, it is possible that a stroke may occur in both cerebral hemispheres at the same time or outside of the cerebral cortex (i.e. in the brainstem or cerebellum) . The right hemisphere is typically dominant in controlling speech and language comprehension (5). It has also been shown to be responsible for the transmission of nerve signals that facilitate swallowing (6). In most left-handed people, as well as a small percentage of right-handed people, the left hemisphere of the brain may control speech and swallowing.

In addition, the part of the brain known as the medulla oblongata links the brainstem with the spinal cord. The medulla oblongata is partially responsible for controlling breathing, blood pressure, heart rate, and swallowing. Any damage to this part of the brain and/or the brainstem can cause an impairment of breathing, heartbeat, blood pressure, swallowing, sleep, and potentially loss of consciousness. A stroke that has extensively affected the brainstem often results in permanent coma or death (7).

Symptoms of Dysphagia

Following a stroke, whether mild or severe, there are some signs that indicate the likelihood of dysphagia. These signs include:

- Pain when swallowing

- Difficulty swallowing

- Sensation of food getting stuck in the throat

- Not being able to chew food properly enough to be able to swallow it

- Drooling

- Coughing or gagging when swallowing

- Taking more time than usual to swallow or consume food items/drinks

Complications of Dysphagia

Dysphagia can have a significantly negative impact on stroke survivors. If a survivor has difficulty swallowing correctly, it can make them less interested in engaging in eating meals. This can cause worsened vitamin, mineral, and nutrient intake that can lead to malnutrition and lowered immunity. If someone is unable to swallow properly, food and drink can enter their airway and travel to the lungs. As discussed earlier, this can cause a specific form of pneumonia called aspiration pneumonia. Saliva can also enter the airway if someone is not able to swallow properly.

Aspiration pneumonia is extremely serious and is the foremost cause of death in stroke survivors that is not directly caused by the stroke (8). For this reason, it is extremely important to get treatment for dysphagia if a stroke survivor suspects they have this disabling condition.

Malnutrition and Quality of Life

Besides dysphagia, stroke-induced facial paralysis can result in excessive coughing or choking while eating or drinking. Coughing helps to clear aspirated material from the airways so it does not reach the lungs, but the stroke often weakens cough strength or air flow/volume (9). Both dysphagia and facial muscle paralysis can lead the stroke survivor to fear eating or even drinking beverages. However, avoiding eating or drinking can lead to a poor nutritional status or malnutrition. Dehydration occurs when fluid intake is too low. This causes a lowered plasma level in the blood which, in turn, can heighten neurological symptoms in stroke survivors (10).

Obtaining a proper level of nutrition and fluids is vital for recovery as a stroke survivor. Up to 62% of all stroke survivors are diagnosed as malnourished in outpatient follow-up, and malnutrition is linked to worsened overall health (11). Therefore a patient may need their meals to be pureed or liquified so more easily digest them, or even try using a feeding tube.

Dysphagia can negatively impact quality of life, as it can be both disabling and prevent someone from enjoying social occasions involving eating. Only 45% of stroke survivors with dysphagia find eating enjoyable, and 41% of stroke survivors experienced anxiety while eating (12). However, through early participation in dysphagia treatment, individuals with dysphagia symptoms can re-acquire nutritional intake ability and capacity. In turn, this can boost quality of life.

Cognitive and Physical Challenges

Experiencing a stroke can affect multiple areas in a stroke survivor’s life, including short-term memory, motor skills, and mental health. If balance has been affected, they may not be able to sit up straight in a chair. This can also impact the ability to swallow food. If their cognition has been affected, they may put more food in their mouth at one time than they could possibly swallow. If their ability to pay attention or concentrate has been affected, they may not notice that they have not opened their mouth to be able to eat when lifting a spoonful of food to it, Swallowing food is a very complex task, and it requires both control over diverse muscles and movements in addition to cognitive processes.

Treatment of Dysphagia

Dysphagia can almost always be improved by treatment if the stroke-induced dysphagia does not spontaneously and quickly resolve. Many stroke survivors who have swallowing problems will receive a referral from their medical providers for sessions with a speech and language pathologist or a swallowing therapeutic specialist, as well as for physical and/or occupational therapy. Therapy aimed at improving swallowing may include learning and practicing the following:

- Physical exercises and cognitive exercises: Specific exercises may improve the motor coordination of the muscles involved in swallowing or enable the central nervous system (CNS) to re-acquire or strengthen the trigger reflex that enables swallowing.

- Swallowing techniques: A patient may learn different ways to place food in their mouth or position their head and body to help swallow correctly.

Depending on the symptoms and severity of dysphagia, different treatment and management approaches are utilized. If the dysphagia is localized to the esophagus, treatments can include:

- Esophageal dilation: For stroke survivors with esophageal muscles that do not contract properly to propel food into the digestive system, a doctor might recommend surgery to dilate the esophagus. During this outpatient procedure, the physician typically uses an endoscope to gently widen the esophagus so food will more easily be propelled through the open structure.

- Medications: Prescription drugs may be prescribed to reduce esophageal spasms (or acid reflux) in order to make it easier to eat meals.

- Diet: A physician may recommend eating a special diet, such as pureed food, so it is easier to swallow.

- Surgery: In some cases, more intensive surgery may be necessary. For example, a laparoscopic Heller myotomy involves cutting the muscle at the lower end of the esophagus when it fails to open so food can be propelled into the stomach.

Speech therapists (also called Speech-Language Pathologists, or SLP) are often involved in dysphagia evaluation and treatment of stroke survivors. During patient sessions, the SLP will typically utilize a combination of compensatory techniques and direct treatment strategies to improve the stroke survivor’s safety in consuming food and liquids, and also reduce the likelihood of food aspiration into the trachea (14).

Managing Dysphagia

The way that dysphagia is managed depends upon the particular symptoms and the severity of those symptoms. Therefore, the treatment and management of dysphagia varies, and what does not work for someone else may still be helpful for another. For stroke survivors with dysphagia that improves but does not disappear over the months following a stroke, there are different strategies and techniques recommended to live safely with dysphagia. The most important strategy is to learn how to eat and drink to be able to eat comfortably without aspiration (i.e. choking). Some of these strategies are described below.

Drinking Safely:

It is very important to drink enough liquid each day to prevent dehydration. However, it can be especially difficult for a person with dysphagia to swallow water or some other “thin” liquid because it is difficult to intentionally prevent these from sliding to the back of the throat. A physical, occupational, and/or speech therapist might recommend using thickened beverages, such as smoothies, to help someone to intake enough daily liquids in their diet. Additionally, thickening powders can be purchased to stir into liquids.

Eating Soft Or Pureed Food:

A stroke survivor may need to eat softer foods to help swallow foods more efficiently. By eating soft or pureed foods, the need to chew is lessened. Since the jaw muscles on one side of the face can be paralyzed due to a stroke, chewing hard food items can be impossible and also dangerous for some stroke survivors in the first few months post-stroke. In turn, this increases the likelihood of attempting to swallow food that is not sufficiently chewed to be properly swallowed. If dysphagia is preventing someone from easily swallowing their food, eating soft or pureed food may make eating easier.

Change The Temperature:

Some hot foods and drinks can be difficult to swallow because they are challenging to comfortably hold them in the mouth for long. A therapist might suggest that a stroke survivor eat meals that are chilled or at room temperature until the ability to swallow hot foods recovers. Avoidance of cold food consumption, such ice cream, may also need to be recommended for a period of time.

Change How And When To Eat:

Eating small amounts of food at each meal may make it easier to eat each meal without experiencing dysphagia symptoms. Therefore, if someone experiences rapid fatigue during meals or struggles to maintain focus while eating, consuming smaller meals can be advantageous. Many stroke survivors find that their sense of taste is diminished due to the stroke, and this can interfere with enjoyment in eating (15). However, it is important to eat healthy meals that are nutrient-rich in order to boost the immune system and overall state of health.

Will Dysphagia Go Away After a Stroke?

Some stroke survivors make tremendous progress and a full recovery from dysphagia. The majority of stroke survivors with dysphagia will recover, but engaging in therapy aimed at dysphagia can play an important role. This is because it can be difficult to figure out how to safely eat in order not to aspirate food while in the early stages of stroke recovery, without the involvement of a professional to help. In the first few days after a stroke, consuming meals while experiencing dysphagia symptoms can be difficult, frustrating, and also promote fear. In turn, this can make someone not want to eat at all, while worsening stroke-related symptoms of depression and anxiety. For this reason, beginning physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy as quickly as possible following a stroke is a good idea.

Some types of dysphagia may require more critical medical interventions than other types. In the case of a complex stroke rendering the stroke survivor with many cognitive and motor skill deficits, following a plan of action for dysphagia recovery can be more problematic. However, someone who is recovering from a less intensive stroke with only slight cognitive or motor skill impacts may only need minimal speech therapy intervention to resolve the stroke-induced dysphagia. While a stroke recovery timeline will be unique to the individual, adherence to a consistent rehabilitation plan can maximize recovery and expedite a return to normal and previously-enjoyed activities.

Role of Rehab Services

While a stroke recovery timeline depends upon unique circumstances and needs, participating in a stroke rehabilitation program can maximize recovery. It can even enable a survivor to acquire greater physical flexibility, strength, and exercise capacity than before the stroke, especially if they did not engage in much daily exercise prior to the stroke. For dysphagia symptoms, a speech or swallowing therapist will assess swallowing skills and provide a patient with their own treatment plan to help maximize their recovery. Following the assessment and creation of the treatment plan, a therapist can also recommend oral exercises aligned with the patient’s impairments that will re-train the oral muscles in the mouth to help improve oral motor control.

Cognitive impairment is common after a stroke, and this includes short-term memory, problem-solving, and decision-making. The memory of simple coordinated movement such as self-feeding can be erased, and exercises prescribed in therapy can promote the return of these memories while enabling re-learning of an essential Activity of Daily Living (ADL). This is equally true of chewing and swallowing. Therefore, one of the goals of the speech and swallowing exercises prescribed will be to engage the brain’s “neuroplasticity” to create new neural networks involved in safely consuming the food in meals. Performing the therapist-prescribed swallowing exercises at home for a specified daily number of times after each therapy session can boost dysphagia recovery speed.

Depending upon the barriers to resolving the swallowing problems and a person’s unique needs, some therapists will perform mirroring of the exercise to the stroke patient while the patient performs the prescribed exercise, so that the stroke patient can follow what the therapist is doing. Other therapies include various exercises to improve oral motor control, massage, or electrical stimulation of muscles via an electrical stimulation machine in which gentle electrical impulses are applied to the muscles around the throat. This stimulates may produce more coordinated movement of the muscles in some stroke survivors with dysphagia.

Navigating Dysphagia: Recognizing Symptoms and Enhancing Stroke Recovery

Knowing and understanding the signs and symptoms of dysphagia can be important for quality of life and overall health status. If a stroke survivor thinks they have dysphagia, obtaining an evaluation from a medical provider is important to entering physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy to resolve this disorder. Crucially, if a physician advises a patient to engage in a rehabilitation program designed to address dysphagia, it is essential to follow through with the recommendation. Avoiding physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy for stroke recovery can result in permanent disability that could otherwise have been resolved. It can also worsen overall quality of life and increase the future likelihood of developing another disabling health disorder.

If medical providers are focused solely on other stroke-caused impairments and not taking dysphagia symptoms seriously, a stroke survivor or their caregiver should advocate for themselves. Treatment of dysphagia can make a huge difference in nutritional intake ability and overall health status. It may be necessary to inform healthcare providers and home-based caregivers of the presence of dysphagia or its severity level in order for them to recognize its adverse effects on the patient. It is possible to improve quality of life even with stroke-caused impairments such as dysphagia by maintaining motivation to recover as much as possible and taking the steps toward resuming activities can boost emotional health.

References:

- Balcerak P, Corbiere S, Zubal R, et al. (2022). Post-stroke Dysphagia: Prognosis and Treatment – A Systematic Review of RCT on Interventional Treatments for Dysphagia Following Subacute Stroke. Frontiers in Neurology 13. (Open access) Webpage: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.823189/full

- Hamdy S. (May 16, 2006). Role of cerebral cortex in the control of swallowing. GI Motility Online (Open access). Webpage: https://www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo8.html

- Stroke Foundation. Swallowing Problems after Stroke Fact Sheet. Webpage: https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-survivors-and-carers/after-stroke-factsheets/swallowing-problems-after-stroke-fact-sheet

- González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, et al. (2013). Dysphagia after Stroke: An Overview. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports 1(3):187-196. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4066736/#:~:text=Dysphagia%20affects%20more%20than%2050%25%20of%20stroke%20survivors.&text=Fortunately%2C%20the%20majority%20of%20these,remain%20dysphagic%20after%206%20months.&text=One%20study%20reported%20that%2080,alternative%20means%20of%20enteral%20feeding.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Right hemisphere damage. Webpage: https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/right-hemisphere-damage/#:~:text=In%20a%20very%20small%20proportion,with%20a%20left%20hemisphere%20lesion.

- Dehaghani SE, Yadegari F, Asgari A, et al. (2016). Brain regions involved in swallowing: Evidence from stroke patients in a cross-sectional study. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 21:45. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5122214/#:~:text=This%20study%20showed%20the%20relation,left%20hemisphere%20in%20dysphagic%20patients.

- Stroke Association. Locked in syndrome after brain stem stroke. Webpage: https://www.stroke.org.uk/effects-of-stroke/locked-in-syndrome

- Armstrong JR, and Mosher BD. (2011). Aspiration pneumonia after stroke: Intervention and prevention. Neurohospitalist 1(2):85-93. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3726080/

- Ward K, Rao P, Reilly CC, et al. (2017). Poor cough flow in acute stroke patients is associated with reduced functional residual capacity and low cough inspired volume. BMJ Open Respiratory Research 4(1):e000230. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5663270/

- Shi Z, Zheng WC, Yang H, et al. (2019). Contribution of dehydration to END in acute ischemic stroke not mediated via coagulation activation. Brain and Behavior 9(6): e01301. Webpage:

- Sabbouh T, and Torbey MT. (2018). Malnutrition in Stroke Patients: Risk Factors, Assessment, and Management. Neurocritical Care 29(3):374-384. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5809242/

- González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, et al. (2013). Dysphagia after Stroke: An Overview. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports 1(3):187-196. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4066736/#:~:text=Dysphagia%20affects%20more%20than%2050%25%20of%20stroke%20survivors.&text=Fortunately%2C%20the%20majority%20of%20these,remain%20dysphagic%20after%206%20months.&text=One%20study%20reported%20that%2080,alternative%20means%20of%20enteral%20feeding.

- UC Davis Center for Voice and Swallowing. [University of California at Davis; Davis, CA]. Anatomy and Physiology of Swallowing. Webpage: http://www.ucdvoice.org/normal-swallowing-physiology/

- University of Maryland Baltimore Washington Medical Center. Dysphagia and Swallowing Therapy. Webpage: https://www.umms.org/bwmc/health-services/rehabilitation/speech-language-pathology/dysphagia-swallowing-therapy

- Heckmann JG, Stossel C, Lang CJG, et al. (2005). Taste disorders in acute stroke. A prospective observational study on taste disorders in 102 stroke patients. Stroke 36(8): 1690-1694. Webpage: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.STR.0000173174.79773.d3