What is Spasticity After a Stroke?

For many stroke survivors, spasticity can be one of the most frustrating and misunderstood aspects of rehabilitation and recovery with little to no effective treatment at times. All forms of spasticity can present a wide range of variables in which the stroke survivor may encounter symptoms such as pain or discomfort related to tightness, decreased coordination, or involuntary movements when attempting volutional use of the arm.

Spasticity is caused by damage to the brain and near pathways or spinal cord following a stroke or hemorrhage. The stiffness of the muscles increases with spasticity. This can cause discomfort in the limb and often inferrers in movement. Pedretti (2006) defines spasticity as “an involuntary muscle contraction below the level of injury that results from lack of inhibition from the brain.”

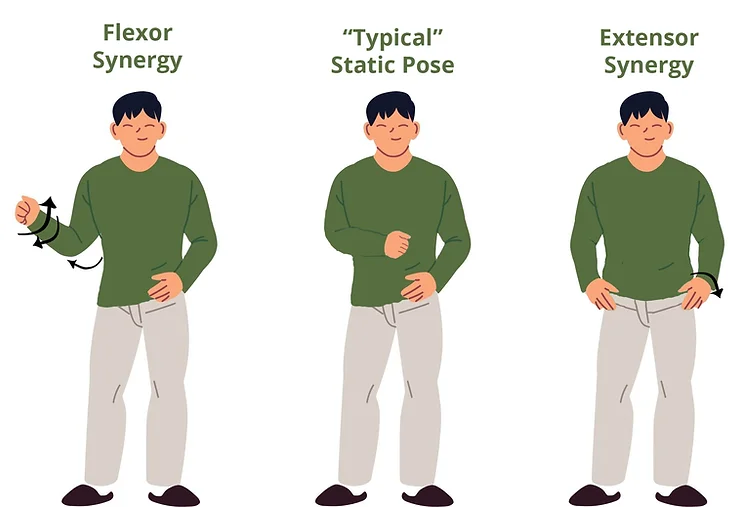

What are Flexor and Extensor Synergy?

Flexor and extensor synergy was first defined by Brunnstrom in the teachings of “Movement therapy in Hemiplegia” in 1970 as the stages of recovery. The progression to weakness or low tone sometimes progresses to a state of increased or excessive skeletal muscle activity known as increased tone or spasticity. Flexor synergy is something that happens often following a stroke due to spasticity.

Synergy vs. Spasticity:

Synergy and spasticity are similar words that have slightly different meanings and are used to describe an abnormal state of an individual’s muscle tone and movement patterns after stroke as a result of the damaged pathways in the brain and spinal cord. As spasticity increases, the risk of soft tissue shortening is heightened. This may lead to a cycle of spasticity (tightness and resistance to stretch). Spasticity often lends to soft tissue shortening due to an over recruitment of shortened muscles because of increased stretch reflexes. This pattern of tightness is called a “synergy.”

Why do Some Experience a Clenched Fist or Stiff Arm After a Stroke?

Synergy often will mimic an arm or leg being drawn in towards the body in flexion or pushing out into extension away from the body. Flexor synergy, otherwise known as spasticity, refers to the muscle “drawing” or “pulling in”, in turn making the muscle in a limb feel stiff, tight, or immovable. The most common areas affected by flexor synergy are elbow flexion paired with shoulder internal rotation, forearm supination, and grasp. Some survivors may express their synergy as a “clenched fist after stroke” with their hand drawing into a fist as if non-purposefully clenched.

Extensor synergy refers to the muscle “pushing away” from the midline of the body as if one is excited. The most common areas affected by extensor synergy are the elbow in extension paired with scapular retraction and depression as well as forearm supination with finger extension.

Please see the below illustration for a comparison of flexor vs. extensor synergy.

Spasticity vs. Voluntary (Volitional) Movements:

Stoke or no stroke, every day we use our body for what is called volitional movements. Volition refers to intended, purposeful, or goal-directed movements. After a stroke, due to hemiparesis (weakness caused by stroke), volitional movements may be interrupted due to damage to motor pathways and neurons. Spasticity or synergy may greatly interfere with the ability to complete volitional movements. Not only can spasticity make it difficult to move volitionally, but purposeful movements can also increase the spasticity itself as spasticity is velocity-dependent. This means that the more movement or speed introduced to the joint, the more the muscles will pull into the synergistic pattern, increasing the tone and decreasing the functional use of the extremity.

Treatment for Spasticity and Flexor Synergy:

As increased purposeful movement occurs and becomes interrupted by spasticity, it is important to implement key treatment strategies which can help normalize the movement. The key treatment strategies focus on sensory stimulation to evoke a motor response, and reflexive movement is used as a precursor for volitional movement. This treatment is directed towards influencing muscle tone (to inhibit or facilitate) developmental patterns, and conscious attention towards the directed movement in order for the individual to understand how to use the spasticity most effectively (Pedretti, 2006). All of these treatments include may include the following, and they may require a skilled occupational or physical therapist to properly provide education and instruction:

- Education on common noxious “triggers” that contribute to heightened spasticity and synergy patterns (i.e. constipation, UTIs, extreme hot or cold temperatures)

- Weight-bearing (i.e. placing pressure through an aligned joint to activate/contract the muscle)

- Gravity assisted movement

- Inhibition techniques that serve to stretch and position muscles and joints in more optimal alignment and for reducing signals that promote over-excitement of neural firing Focus on trunk and extremity positioning

- Active assisted movement

- Functional use of the extremity

- Electrical stimulation (combined with function or used to relax the spastic muscle groups)

- Medication management such as Botox or Baclofen (please speak to your physician if you are interested in this option)

For upper extremities with little to no movement, inventions like splints and the Neurolutions brain-computer interface IpsiHand system can be effectively paired with traditional therapy with the occupational therapist to address activities of daily living, family training, use of adaptive equipment, and the use of one-handed techniques with the use of assistive devices. Please speak with your occupational therapist or physician to discuss all treatment options as part of a comprehensive spasticity management program that may include multiple specialists

References:

Pendleton and Schulta-Krohn (2006) Pedretti’s Occupational Therapy Practice For Physical Dysfunction: 6th Edition. New York, Elisver.